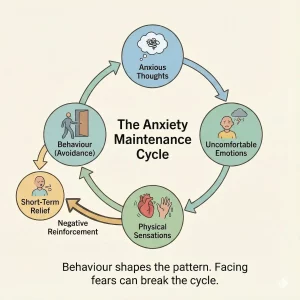

When people experience anxiety, their behaviour is often shaped by powerful patterns that develop without conscious awareness. These patterns can quietly sustain anxiety in much the same way that thoughts, emotions, and physical sensations interact in a maintenance cycle. This article adds a fourth element, behaviour, to that picture, showing how what we do or avoid doing can keep anxiety alive.

When we feel anxious, our minds and bodies are flooded with sensations that are uncomfortable. Our natural instinct is to move away from things that feel punishing and towards things that feel safe or pleasant. Behaviourism, a branch of psychology that studies how behaviour is learned, helps us understand this process.

At its simplest, behaviourism tells us that our actions are shaped by what happens immediately after we do something. If an action brings relief, comfort, or pleasure, we are more likely to repeat it. If an action leads to discomfort or distress, we are less likely to do it again. This is the basic idea behind reinforcement.

Positive and Negative Reinforcement

One important idea is called negative reinforcement. Despite its name, it does not mean punishment. It means that when something unpleasant is removed, it strengthens the behaviour that came before it. For example, if a person feels anxious about meeting new people and decides to cancel a social plan, they may feel an immediate sense of relief. The uncomfortable sensations of anxiety lessen, and this relief acts as a reward. Without realising it, the person learns that avoidance works, at least in the short term.

Over time, this pattern becomes self-reinforcing. The more often a person avoids what makes them anxious, the more convinced they become that the situation itself is dangerous or unbearable. They may also begin to believe that they cannot cope with difficult emotions or tolerate uncertainty. In this way, avoidance not only maintains anxiety but helps it grow, spreading into other areas of life as the brain learns to associate more and more situations with threat.

The Power of the Actions We Take

From a behavioural point of view, the maintenance cycle now includes a fourth component alongside thoughts, feelings, and physical sensations: the actions we take. Understanding this link allows us to see that anxiety is not just something that happens to us but something that is influenced by what we do in response to it.

In therapy, you can begin to notice these behavioural patterns, see how they connect to the emotional and physical parts of anxiety, and experiment with small changes. Over time, facing feared situations gradually and in a structured way, rather than avoiding them, allows you to relearn safety and confidence. What was once an automatic and fearful cycle can slowly become a process of growth and mastery.

To understand why avoidance feels so powerful and how it shapes what we learn about fear, see the related article “Learning Theory and the Roots of Anxiety”.